10 underused features of modern Python [incomplete]

Named tuple

from typing import NamedTuple

class EnvParams(NamedTuple):

name: str

nr_agents: int

mode: Literal["uniform", "relative"] = "uniform"

def get_params() -> EnvParams:

return EnvParams(name="hello", nr_agents=42)- automatic constructor generation etc

- strong typing

- immutable

- same memory usage as normal tuples

- default values

- more safety than tuples, access

params.namelike objects, order does not matter - compatible API with tuples

Typing

A must if you’re used to typed programming languages. Makes it much easier to read and understand code, as well as fixing a whole class of bugs.

Let’s say you have some simple code to print a list of words:

def show_words(list_of_words):

for i, word in enumerate(list_of_words):

print(f"word {i}: {word}")> show_words(["hello", "hi"])

word 0: hello

word 1: hiEasy enough, right?

But what happens if that code is accidentally called with a string?

show_words("hello")

word 0: h

word 1: e

word 2: l

word 3: l

word 4: oSince iterating works for strings as well, the code works - but not as expected. In this example the issue is easy to find, but if for example you have a multidimensional list where each text is processed in some way and passed further along into a neural network, you might not find this issue for a very long time.

It’s even worse because in python, chars are strings as well (e.g. "a"[0][0][0] == "a"), so you can have a nested loop of any depth that will still work when receiving a string.

The solution is simple:

def show_lists(words: list[str]) -> None:

# if you try to call this function with anything

# that's *not* a list of strings, your IDE (and mypy)

# will throw an error.F-strings

There’s many ways to format strings in python, with the original one being % formatting. But the best way since Python 3.7 is literal f-strings:

def fn(x):

return x * x

x = 5

print(f"for input {x:.1f}, {fn(x)=}")Prints: for input 5.0, fn(x)=25

Similar to "x is {x}".format(x=x) but easier to read and write. You can add simple expression inside the {}. The special format specifier f"{foo=}" is the same as doing f"foo={foo}"

Pathlib

from pathlib import Path

mydir = Path("foo")

myfile = mydir / "filename.txt"If you pass file paths around as strings, you have to figure out when to add slashes and when not to, and unless you always use os.path.sep your code will work differently depending on the OS. With pathlib, you can join paths using just the / operator, regardless of the OS of the user.

Paths have great methods for manipulating filenames that are much more readable than their os.path equivalents:

myfile = Path("foo/filename.txt")

myfile.parent # Path("foo")

myfile.name # "filename.txt"

myfile.suffix # ".txt"

# replace file extension

myfile.with_suffix('.csv') # foo/filename.csvPaths also have neat methods for opening / reading / writing files:

myfile.write_text("hello")

if myfile.exists():

with myfile.open("r") as f:

# ...

pass

text = (mydir / "input.txt").read_text()

for file in Path("foo").glob("*.txt"):

# every txt file in foo/

passRelative imports

The following is fairly common python code:

import util

util.foo()But what is util? It can be either a global module or a local file / directory. If there is a local file named util.py, it will shadow the corresponding module. This is a pretty common issue, and happens even to experienced devs.

Instead, in my opinion you should always use relative imports if you want to import a relative module instead of global ones.

from . import util

# or

from .util import fooSadly this ambiguity issue is not completely fixeable without a breaking change in python itself, and due to a bad design decision in the Python module system relative imports have some issues when python files are loaded in a specific way called "script mode", which you will probably come across sooner or later.

Ordered unordered dicts

Since Python 3.6, Python uses a more compact representation of dicts (and thus kwargs). Since Python 3.7, it is guaranteed that dicts are always iterated over in insertion order.

This means that every dict is basically an OrderedDict except some utility functions are missing. This is really useful, because it means you can use normal dicts as ordered associative arrays.

x = {

"c": True,

"b": False,

"d": False

}

for key in x:

# guaranteed to always go through keys in the order "c", "b", "d"!Multiprocessing

There’s a ton of libraries for multithreading / multiprocessing in python, with varying degrees of magicness. But in Python 3, there’s actually an integrated way to run a function on a large set of data quickly: multiprocessing.Pool

def f(x):

# expensive computation

return x * x

from multiprocessing import Pool

with Pool() as p:

for result in p.imap(f, [1, 2, 3], chunksize=100):

# ... handle resultThis code does the same as for i in [1,2,3]: f(i) except using all your CPU cores.

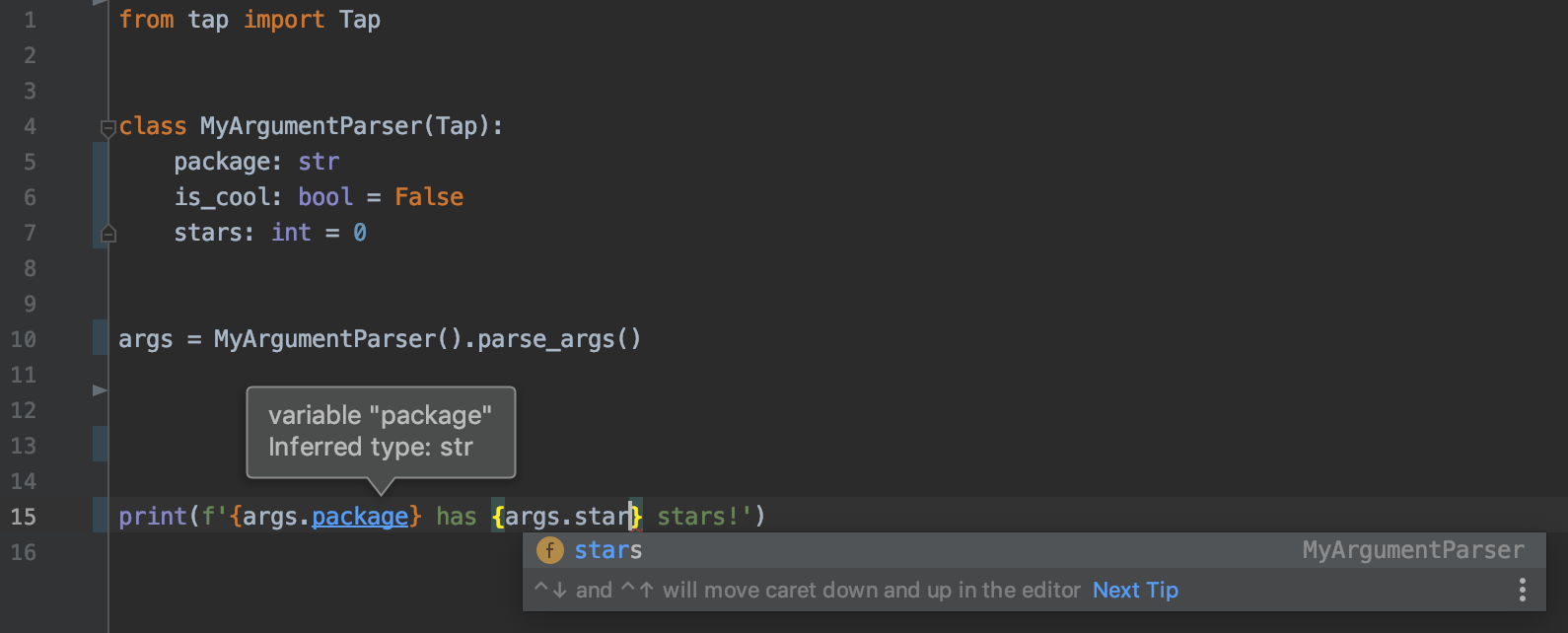

Typed Argparse

Argparse is a neat library to create a simple command line interface. But arguments are declared as strings, and the IDE can’t know about them.

With Typed-Argparse, your arguments are parsed directly into a class instance! It’s a separate library, not integrated in python like argparse, but it’s much neater.

Poetry

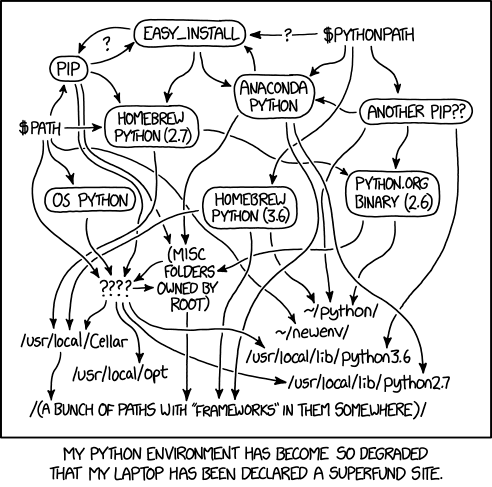

Here is all the stages of a Python developer’s slow decent into madness:

You write single file .py scripts without imports and functions. It’s so easy to get so much done! You feel enlightened.

You start splitting your code in multiple functions in .py files, and feel enlightened of how structured your code is now.

You need to do some maths, so you learn about

pipand runpip install numpyglobally. You feel enlightened about how easy it is to use libraries. It’s as easy as import antigravity!At some point you have some multiple projects that need different versions of some libraries. You learn about virtualenvs. You are confused about the difference between

venv,virtualenv,virtualenvwrapper, but some random memorized commands works so you start using virtualenvs.You try to use some older library from GitHub. You learn about

setup.pyfiles andrequirements.txtfiles, and you feel enlightened! This is how you define exactly what you need to run your program! The project you’re trying to use has a requirements.txt file like this:pandas numpySo you eagerly run

python -m venv .venv source .venv/bin/activate pip install -r requirements.txtThen you try running the project, but it turns out it actually also needs

sklearn. So you trypip install sklearnonly to realize thatsklearnis actually a random package from someone else and to getsklearnyou actually need to installscikit-learn. You realize that package names are not actually related to the names of python modules (except incidentally) and feel enlightened by the power!But the code still doesn’t run, theer’s some weird issue. After an hour of investigation, you find some obscure bug caused by an incompatible change some time 5 years ago in numpy. You try some old numpy versions until you find one that works. You learn about semver and freezing, and you feel enlightened! The developer should have just put

numpy==1.10into their requirements.txt!You find something that recommends using Conda. You are somewhat confused why the conda download is taking so long and eating up 2GB of bandwidth. After accepting a random EULA and having your shell changed prompt always say

(base) $, you realize that in conda, everything is an env! It’s so quick to add libraries, even weird native ones ! You feel enlightened.You read some documentation and call a python function, but the function does not exist. After some reading, you see that the package you installed via conda is an outdated version. You now understand that conda is a completely different package manager from pip, and that conda packages are actually managed by third parties, some of which are outdated, and many don’t exist at all. You start using

pipfor some things andcondafor other things, all in the same environment. Sometimes you randomly add-c conda-forgewhen conda install doesn’t work.The find out about the Official Modern Python Packaging tool pipenv! Pipenv always and automatically manages a virtualenv with the exact dependencies as defined in a

Pipfile, which is like a superchargedrequirements.txt. It’s amazing! Except you soon try to install a package and get aCould not resolve dependencieserror. You google a while, and figure out that most pypi packages don’t actually have correctly specified dependencies, and that pip just doesn’t really care about that. You also find out that pipenv only really pretended to be an official tool.You find out about poetry. It’s like pipenv but actually fairly good! It only takes 2 minutes to resolve dependencies instead of 10! It even puts your virtualenv in

~/.cachebecause it really doesn’t matter if it gets deleted!A while later you find the latest development of python dependency management: pyflow and pdm. It uses the same standard

pyproject.tomlformat as poetry, but it puts your dependencies in a./__pypackages__directory so when running stuff you don’t have to care about activating a virtualenv or always usingpoetry run python. … Wait, isn’t that literally just node_modules? The thing JS devs have been complaining about for a decade?

Tl;dr: